Moody’s Investors Service has cut the long-term sovereign rating of the United States by one notch to Aa1, citing the inexorable rise in federal deficits and debt-servicing costs at a time of still-elevated interest rates.

The decision, made public just after market close on Friday 16 May, leaves the world’s largest borrower without a triple-A from any of the “big three” agencies. Standard & Poor moved first in 2011, Fitch followed in 2023, and now Moody’s has closed the chapter.

Several developed countries including Australia, Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Sweden and Switzerland retain a triple rating from all ‘big three” rating agencies.

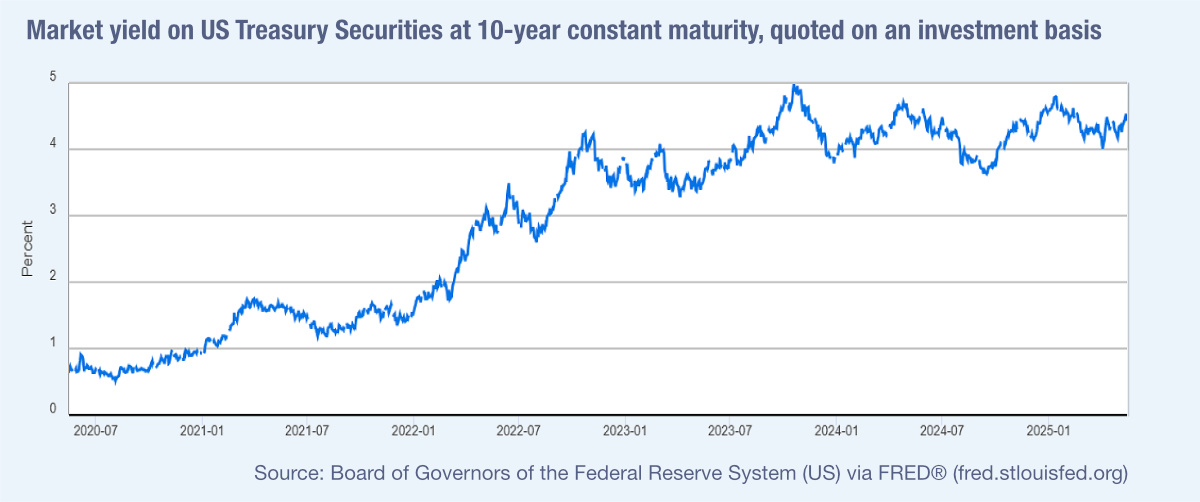

Ten-year Treasury yields briefly jumped nine basis points to 4.53% in the immediate aftermath, but the sell-off soon faded.

Solita Marcelli and Mark Haefele, respectively global wealth management chief investment officer for America and worldwide at UBS wealth management, argue in a note from 19 May that investors were already aware of Washington’s fiscal path: “Significant selling of US Treasuries is unlikely […] while yields may move 10-15 basis point higher in the short term.”

Most portfolio mandates do not insist on a triple-A badge, and Treasuries remain the world’s deepest pool of collateral accepted by central banks, as well as the lowest yielding and safest US dollar asset; a key reason the downgrade failed to spark forced liquidation.

Rabobank’s senior US strategist Philip Marey offered a similar verdict. He wrote in a note published 19 May: “[The move] does not tell markets anything they did not know and, in fact, recent movements in Treasury yields and the US dollar may be of more concern than the official downgrade.”

In other words, price action had already incorporated the heavy supply pipeline and the Federal Reserve’s slower-than-expected easing cycle.

Moody’s criticism centred on a federal budget deficit now running above US$2 trillion, or more than 7% of GDP, even with unemployment near historic lows.

Net interest expenses represent 18% of tax revenue; that share is set to climb if rate cuts arrive slowly. Yet, as UBS notes, the United States still enjoys very high credit quality thanks to the dollar’s reserve-currency role and the breadth of its domestic savings pool.

For dealers underwriting Treasury auctions, the question is whether a lower rating across all big three agencies translates into higher concession or weaker bid-to-cover ratios. The consensus amongst analysts is that any impact will be marginal.

UBS rates strategists Reinout De Bock and colleagues observe that: “The market reaction to the Moody’s downgrade of US debt to Aa1 is another indication that the end of the steepening theme likely remains far away, as central banks ease, elevated volatility boosts risk premiums, and supply remains high. We see limited regulatory impact of the downgrade.”

According to UBS, auction participants would still treat Treasuries as the risk-free anchor; there is no rule change that would force banks or money-market funds to demand higher coupons simply because of Moody’s decision.

The same team at UBS expects the 5-to-30-year bond spread to keep steepening as heavy coupon supply collides with a few near-term expected Fed cuts. That shape matters for issuers, because the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee has already flagged a preference for more long-bond issuance to lock in today’s yields.

Asian reserve managers, US pension schemes and insurance companies continue to buy duration for regulatory or liability-matching reasons. None of those constituencies require triple-A paper.

In 2011 the first triple A cut by S&P stirred heated debates in Washington and a far larger market reaction; in 2025 the political fallout is, so far, a lot more limited. But the direction is similar: Overseas market reacted to the news only for it to be corrected during US trading hours; while equities and bonds traded markedly lower in the Sunday overnight session, they rallied back after the US open.

“Credit downgrades are less politically costly in the US than you might think,” the UBS team reminds clients. For primary markets the verdict is similar: the downgrade does not alter the mechanics of financing a government that must sell more than US$3 trillion in new net issuance over the 2025 fiscal year.

©Markets Media Europe 2025