Participants say electronic trading of Japanese government bonds has reached an inflection point, but others counter that the death of voice trading has been overexaggerated.

By Nick Dunbar

If there is one area where changes in Japan’s financial markets are likely to be consequential, it is the government bond market. The country is an outlier among developed nations, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 230%, which would be devastating for most economies but has long elicited a shrug when it comes to Japan. With JGB yields close to zero, the interest burden was easily manageable, and most investors were domestic, reducing the risk of capital flight.

Now, these time-honoured truisms are going out of the window. Inflation is up, the yen has weakened to a near-record low against the dollar and JGB yields recently hit a 17-year high. The Bank of Japan has reversed its long-standing quantitative easing policy and its holdings of JGBs are falling at a rapid pace. With the country’s first female prime minister Sanae Takaichi announcing stimulus measures, foreign investors are entering the market, attracted by the competitive yields.

This internationalisation of JGBs is shaking up what used to be a sleepy trading community in Japan. At Sumitomo Mitsui (SuMi) Trust Asset Management, which has $633 billion under management, trading group manager Yasunori Ejiri told Global Trading, “I don’t think there is any fundamental difference between Japanese and international bond trading but I do think that the long period of zero interest rates due to the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy created a closed environment for bond trading.”

Those days are now over, according to Toshifumi Niwa, head trader at Nissay Asset Management Corporation, which manages $272 billion, including active bond mandates for Japan’s $1.5 trillion Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF). “Electronic trading systems have become essential for the buy side of the current JGB market,” he said. “On a ticket-based basis, approximately 80% of our JGB trading is executed electronically.”

Ejiri offers similar statistics. “According to our most recent data, electronic trading of JGBs has increased to approximately 90% in terms of notional volume and 60-70% in terms of transaction volume.”

This electronification hasn’t come from nowhere. According to figures from one trading platform, $95 billion of JGBs are traded electronically every month, up from $20 billion per month in 2020. However, this is still a small fraction of the $1.6 trillion of JGBs traded over-the-counter each month, according to data from the Japan Securities Dealers Association.

Buyside traders in Japan talk about the user-friendliness of going electronic, noting that the surge in remote working during the 2020-21 Covid pandemic prompted many to begin screen trading for the first time. Rather than use Yensai.com, the domestic Japanese JGB platform which Niwa describes as ‘less user-friendly’, traders opted to use Tradeweb.

“Since the Covid-19 pandemic, I believe that the progress made in digitisation has been largely due to the fact that traders in particular are now able to use user-friendly systems,” according to Niwa. “For example, if you have experience trading foreign bonds and have used Tradeweb, you will be able to trade JGBs smoothly.”

Another driver of electronification has been increased use of interest rate derivatives, Niwa explains. “For companies like ours that trade a lot of over-the-counter derivatives, mainly interest rate swaps, we feel that being able to trade on the same screen as JGB is a huge advantage.”

With the record highs in JGB yields, buyside firms are racing to add swaps to juice returns on low-yielding legacy portfolios, said SuMi Trust AM’s Ejiri.

“Swaps are increasingly being positioned as a source of return rather than a hedging tool, and the swap market is growing alongside the advancement of electronic trading,” he said. “Unfortunately, our company has been slow to adopt asset swaps and we would like to catch up in the future.”

Meanwhile, sell-side firms in Japan also note the benefits of electronic trading. According to Ejiri, the ‘big five’ securities companies that dominate market making for bonds are Nomura Securities, Daiwa Securities, SMBC Nikko Securities, Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities and Mizuho Securities.

At the last-named firm, head of macro trading Takashi Kitsukawa shares his experiences. “For us, electronic trading has been growing rapidly over the last 5-6 years. First, e-commerce sales are supporting electronic trading. Customers can execute transactions smoothly. From an IT perspective, we are placing the IT development team on the trading floor. In this way, awareness has increased significantly.

“In terms of operational costs, JGBs include a large universe of bonds, so when it comes to inquiries such as executing many bonds at once, electronic trading is clearly more advantageous. It doesn’t require any trader’s help. This is extremely good for us. Then, if the risk amount or size is to a certain extent, then pricing using algorithms is the way to go. Or auto-hedging using futures will become effective.

“Finally, information is the biggest benefit. Our systems can accumulate transaction data, analyse it, and utilise it. This includes data on transactions that did not result in a trade or market.”

Risks of going electronic

Yet for all the advantages of electronic trading, as soon as participants plug themselves into it, they encounter a new world that moves at breakneck speed. As Nissay AM’s Niwa puts it, “From the buy side perspective, one of the risks of electronic trading is the increased speed. At the moment, I think this has both positive and negative aspects.”

This speed makes electronic trading something of a self-fulfilling prophecy – if electronic trading is risky, it might be even riskier not to trade electronically when markets move fast, as Niwa puts it. “In the JGB market today, the speed from the start of an inquiry to a deal has improved, and there are more and more cases where companies choose to trade electronically in order to shorten the time their orders are exposed to the market.”

“In the spot interdealer market, order book formation continues to be mostly done through manual input, and even from the buy side, we can see situations where order book formation in the spot interdealer market is not keeping up with price fluctuations in futures. In other words, the higher the volatility, the more likely the price will disappear. Therefore, voice transactions, which take time, carry increased risk.” In this environment, “electronic trading has become indispensable,” Niwa explains, as he outlines all the steps needed for a voice trade.

“When conducting voice trading, we output text from our internal system to be pasted into Bloomberg Chat. We copy it, select the chat room of the person we want to contact, paste it, and then make the inquiry. The sell-side salesperson then takes a picture of the price and types it into the chat room. We traders then visually determine the best price and communicate our desire to execute via electronic phone or chat.”

This manual procedure wastes precious time, Niwa points out. “While we are carrying out this type of work and communicating, the market is constantly moving, and we often find ourselves in situations where, when we want to execute a transaction, the price we want to trade at is no longer available.”

In Niwa’s view, this is because equity-like behaviour from HFT-riddled futures markets affects bonds too. “We believe that one of the reasons for the increased speed of electronic trading is the influence of the JGB futures market,” he says. “The futures market is becoming increasingly electronic in a manner similar to that of the stock market, and we believe that many market participants are trading using direct market access (DMA) trading, or so-called algorithmic trading. When futures prices move, it affects the spot market price.”

On the sell-side, Mizuho’s Kitsukawa also sees this self-fulfilling prophecy at work. “As electronic trading advances, market transparency increases. However, as a side effect, when a large transaction goes through the market, the information spreads to the market in an instant. As a result, price movements lead to more price movements.”

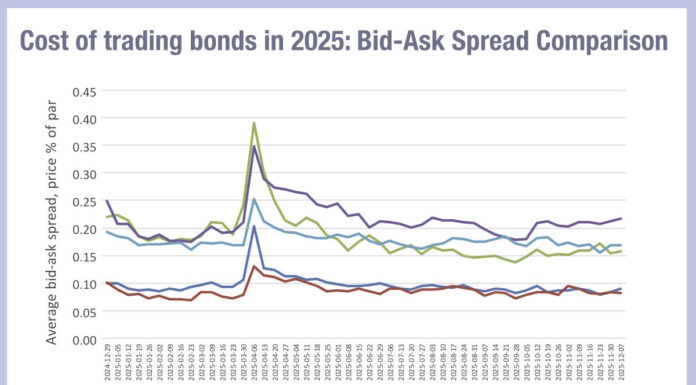

And electronic market makers are unwilling to absorb these endogenous shocks, he says. “The sell-side’s discretion and risk-taking power are what normally absorbs the flow. I think this is declining a bit. If the spread between offer and bid is unstable, then trading volume will be unstable. I think we need to recognise that the behaviour of the sell-side is undergoing structural changes, which in turn is affecting price movements, as one of the risks of electronic trading.”

The persistence of voice trading

Amid such concerns, practitioners argue that voice trading still remains essential. For a start, there are plenty of buyside use cases that can’t be handled, either by the electronic trading platform or the user’s order management system.

“For transactions that are not supported by electronic trading, the only option is obviously voice trading,” Niwa says. “In addition to methods that are not supported by the electronic trading platform, voice trading is also an option for methods that are not supported by the order management system (OMS) that we use.”

“This situation occurs when transactions that involve multiple sets of bonds, such as basket trading in which multiple bonds are traded on an all-or-nothing basis,” he explains. “Additionally, even if electronic trading is possible, there are cases where people choose to trade by voice. These include transactions that are large in size, such as 10 billion or 20 billion yen, and are likely to have a market impact.”

Another situation that justifies voice trading is where buyside traders are part of a three-way conversation involving the sell side and portfolio managers. “In many cases, buying and selling is carried out through communication with the dealer’s sales staff and then with the fund manager within the company based on the price presented,” Niwa says. “The disadvantage of electronic trading is that all parties to an inquiry must be decided at the time of initiating the inquiry, which means that it is difficult to add parties to increase the price midway. As a result, once all price offers are in place, it is necessary to immediately decide whether or not to execute the transaction.”

From the sell side, Mizuho’s Kitsukawa points out that there are a swathe of buyside firms that are natural users of voice trading as the BOJ reduces its gargantuan portfolio. “Bank deposits have an enormous presence, and I believe this is a unique feature of the Japanese market that is not found in Western markets,” he says. “That is why I think that domestic banks are considered the most likely entities to replace the Bank of Japan as the main owners of JGBs. As a result, banks now have an extremely large presence in the secondary market, and price formation in the JGB market.”

“Because of their large presence, even adjusting their positions can have a significant impact on the market,” Kitsukawa continues. “Rather than focusing on speed of execution, we need to ensure solid liquidity and execute transactions steadily. This has to be a priority, so we need voice dealers who can handle large-scale transactions.”

And Kitsukawa is clear about what the sell-side requirements are – the kind of hefty balance sheet and proprietary acumen that electronic trading has placed under threat. “What is required is the ability to handle large tickets while minimising the impact on the market, which means the courage to withstand short-term market fluctuations, the ability to determine whether a price is a temporary distortion or fair value, and the franchise or drive to find the opposite flow that will offset the risk.”

Improving technology and hiring talent

One thing that both buyside and sell-side agree on is the need for people. “The spread of electronic trading has not only brought about changes in trading methods, but also it is changing the type of personnel the market is looking for,” says Nissay AM’s Niwa. “In addition to intuitive skills such as experience and intuition, as in the past, the ability to make decisions based on data, such as algorithms and quantitative analysis, is becoming essential on both the sell-side and buy-side sides.”

Mizuho’s Kitsukawa explains how the sell-side JGB desk is changing. “Our trading room dealers are made up of senior voice dealers and young quantitative AI experts, which creates a barbell-like portfolio, and I hope that this extreme mix of personnel will create a good chemistry. In any case, I think it’s a very welcome development that new talent has entered the JGB market.”

An example of why these changes are necessary is that a new breed of traders is needed to handle tools being offered by vendors. “From the buy-side perspective, our company uses AiEX, an automatic ordering function developed by Tradeweb,” notes Niwa. “The decision on whether to use AiEX is based on quantitative analysis. So, should you use voice trading, electronic trading, new execution methods such as automated ordering, or trade in combination with other products?

“Advances in technology have given us more options than ever before. In this situation, we believe that quantitative judgment will become even more important in the future, also from the perspective of accountability to final investors, and we believe that there will be a strong demand for such personnel on the buy side as well.”

This article forms part of the joint Global Trading & The DESK Special Report on Japan. To download the full Japan Report click on the image below:

©Markets Media Europe 2025