The phrase ‘Don’t Panic’ crops up frequently in comic fiction, notably in Douglas Adams’ book ‘Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’ and in 1970’s British sitcom ‘Dad’s Army’. It is typically used to comic effect by presenting in a situation which exemplifies the urge to panic.

With concern about the economy ringing around markets, led by Jamie Dimon’s hurricane warning, “You better brace yourself,” it is worth bearing ‘Don’t panic’ in mind when considering where the props might get kicked out from under weak players.

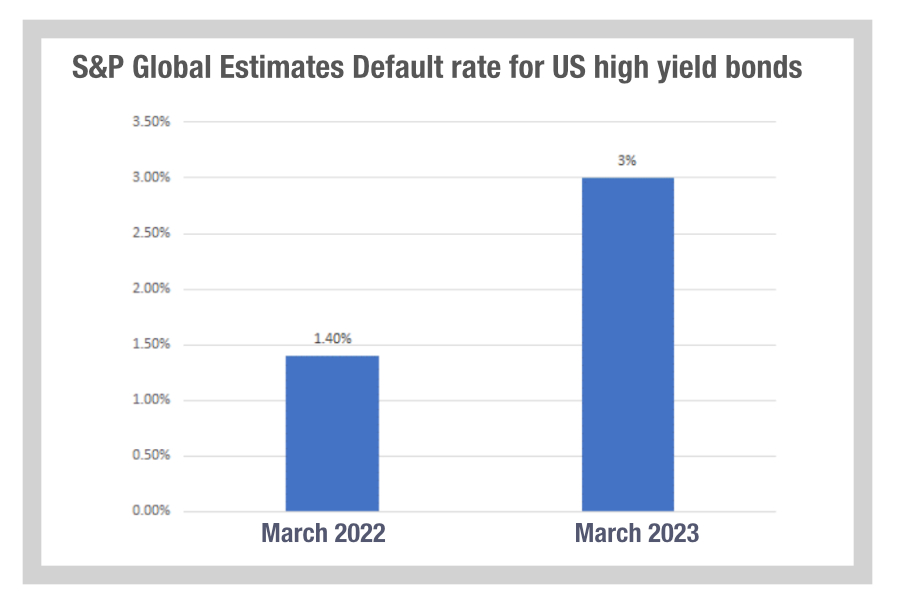

S&P Global is currently estimating the corporate default rate for US high yield (HY) bonds over a 12 month period to hit 3% by March 2023, up from 1.4% in March 2022, a rise that would require 57 high yield bond issuers to default. This year has seen CCC-rated US credit fall in value as investors divested themselves of riskier assets, concerned the higher returns could be outweighed by the risk of default.

With market volatility high, significant macro events impacting investor appetite and trade, alongside central banks having a thankless task in managing inflation while upsetting markets, there are many potential triggers for an unexpected event.

However, I would suggest the greater risk to investors at least is not in defaults by firms with weaker credit ratings. I have witnessed many crises in the past which have threatened the financial system, but several stand out: Enron and the subsequent corporate governance crisis; the 2007 credit crisis and Lehman default triggering the global financial crisis; the Madoff Ponzi Scheme. All of these have weakened confidence in the system, and changed governance requirements, but most significantly each was unexpected.

Enron’s accounting was audited by Arthur Andersen, a big five accounting firm which dissolved afterwards in the face of the massive fraud, leaving the big four.

Lehman Brothers used trick accounting, audited by big four accounting firm EY, to hide US$50.5 billion in debt using a repurchase agreement mechanism, which was revealed as the bank foundered, and subsequently defaulted.

Madoff (audited by two-person accounting outfit Friehling & Horowitz) simply lied to investors about investing their money.

In each case – Enron during the dotcom crash, Lehman and Madoff during the credit crisis – a major market disruption was made worse by lying and fraud. Lehman’s accounting was certified ‘legal’, but potential buyer Barclays would not do so without government backing of its risk, which it could not obtain.

The fact is that, even in the worst credit events, it is possible for investors to manage risk. As defaults increase there will be real-world effects for the employees and companies which will be hard to take. To some extent these are predicable.

A greater risk is concealed risk – typically on the balance sheet – which can prevent either investors or a company’s directors from managing it.

Rising defaults are bad, but don’t panic. Unless there is fraud.

©Markets Media Europe 2025