By Evan Brown and Meena Bassily of UBS Asset Management

Consensus growth forecasts for the US and other advanced economies have been

repeatedly revised higher since Liberation Day for both 2025 and 2026. We still think a 2%

US GDP forecast for 2026 is too low.

Two key factors have contributed to the surprising strength in the US economy. First,

business and consumers have proven more resilient and adaptive to shocks than expected,

particularly tariffs, due to corporate dynamism and strong balance sheets (see Macro

Monthly: The key to this cycle’s resilience). Second, the scale of AI-related capital

expenditure and investment has been significant, and in part, related to this – productivity

growth may have been underestimated.

Indeed, the Fed has made back-to-back upward revisions to its growth forecasts in its last

two quarterly projections. The central bank’s latest outlook points to stronger growth in

2026 with limited inflationary impact, which Fed Chair Powell attributed to a rebound

from the recent government shutdown and rising expectations for AI capex. We share this

optimistic view and think the prospect of a higher-productivity regime – one that could

deliver stronger real corporate profits and boost real incomes – presents an upside risk to

an already strong outlook.

Several factors have contributed to higher productivity growth. The pandemic forced businesses to operate more efficiently, and this was compounded by a tighter labor market in 2022-23. After the pandemic, businesses benefited from reworked supply chains, deepening capital, and digitization, among other dynamic shifts. Looking ahead, we think AI will play a role in driving further productivity gains.

Estimating the scale and speed of AI’s impact on productivity is challenging, as we are still in its foundational phase and many variables affect productivity. While there have been several theoretical simulations – which agree on AI’s transformational potential but disagree on the scale and speed of its impact, (e.g. from the IMF, OECD, McKinsey) – we are now starting to see real data. The St. Louis Fed’s Real Time Population Survey, which asks US workers about AI usage, estimates that AI has increased labor productivity by up to 1.3% since ChatGPT became available. They also find industries with high AI-adoption are growing faster than their pre-pandemic trend.

The extent to which AI can support economic growth and future earnings of companies is perhaps the most important – and challenging question – for investors this year. We have observed greater dispersion in performance of megacap tech, which we view as healthy insofar as it indicates greater scrutiny of company-specific dynamics and is not characteristic of irrational and indiscriminate bidding behavior typically associated with market bubbles

Aside from the potential for a higher-productivity regime, we believe the combination of easy financial conditions, healthy private-sector balance sheets, and signs of improvement in manufacturing suggests we’re starting the year on solid footing. On top of that, US fiscal legislation passed last summer is set to provide a $55 billion boost to US disposable income in coming months through tax rebates.

Ex-US, the outlook has improved as policy rates approach near neutral, fiscal stimulus rises in major economies (including Germany and Japan), and trade uncertainty diminishes. Business confidence is improving, and the global composite PMI signals expansion in new orders and future output across manufacturing and services.

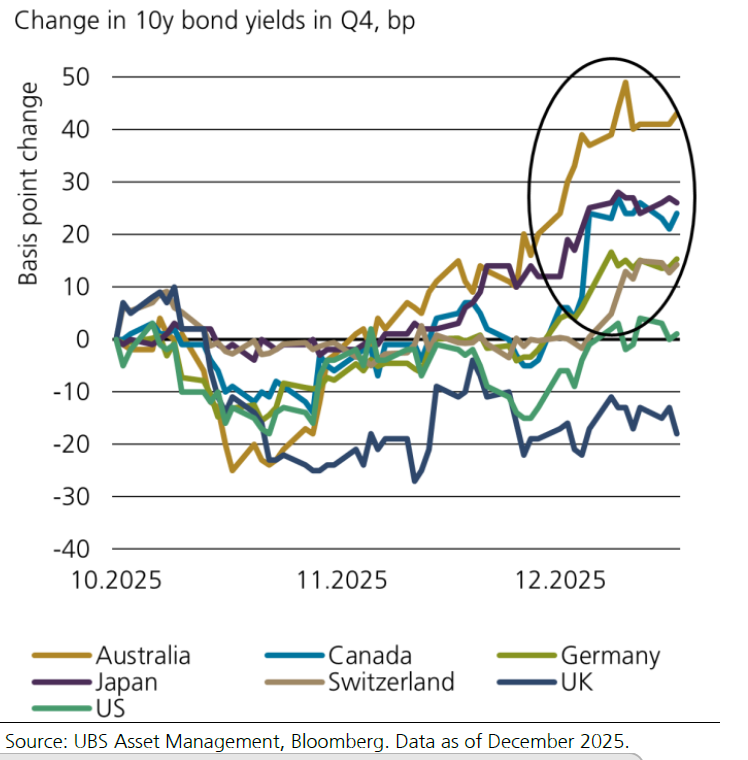

Against this backdrop, markets enter the year pricing some probability of rate hikes across several advanced economies by Q4, and both short term rates and bonds point to an improving 2026 growth outlook.

The politics of inflation

While it is typically reasonable to expect that stronger growth might lead to a sustained rise in inflation, we think the current environment is less conducive to a surge in inflationary pressures. In the near term, inflation may see a seasonal uptick in Q1 – as has occurred in recent years – and could be amplified by delayed tariff pass-through after holiday price reductions. However, we still think risks to consensus inflation forecasts – at 2.5% 2026 Q4/Q4 for core PCE in the US – are skewed to the downside due to several factors which suggest that this near-term inflationary impulse will likely to be temporary.

First, political incentives are strongly aligned toward containing inflation. The Trump administration has faced electoral setbacks in off-cycle elections and polling points to affordability concerns as a key driver of voter dissatisfaction. These concerns are shaping policy priorities ahead of the November midterm elections.

Already, tariffs have been removed on several imported groceries not grown in the US, and tariffs on China have been reduced. We expect upcoming trade policies to be implemented with a focus on reducing, not increasing, inflation.

Second, sustained demand-led inflation typically requires a tightening labor market and upward pressure in wages. While we expect growth to remain robust, it’s unclear whether the labor market will reaccelerate, as AI-related capex has not been additive to employment growth and AI adoption may slow hiring. In addition, shelter inflation, which accounts for about a third of the CPI basket, has been decelerating and alternative rent measures are running below their pre-pandemic trend.

Third, China is exerting a deflationary impulse. In 2025, Chinese export volume growth has outpaced the rest of the world by a margin not seen since 2001, while export prices have fallen sharply. This reflects excess manufacturing capacity – partly due to tariffs and weaker domestic consumption – and China’s unique position to combine strong manufacturing capabilities with technological advancements and AI adoption.

©Markets Media Europe 2025