Someone, somewhere, is cooking the books

In 2007, I explained the risks of cumulative capital market investments to a friend as a series of interconnected poker games in which each table’s stakes were being supplied by the assumed winnings of several other tables.

If the stakes in one game are exposed to be ‘counterfeit’, lots of other games discover they are playing with ‘counterfeit’ stakes too, and this loss ripples across the tables.

I say ‘counterfeit’ but inevitably, under pressure, someone’s accounting will prove to have inflated or hidden a material number that makes everyone’s sums go wrong. Think Lehman Brother’s hiding of balance debt using a reverse repo transaction – it does not have to be criminal, just misleading, for investors to discover a number they think they know, “…just ain’t so,’ in the words of Mark Twain.

Real money will be lost betting on an incorrect number. A sale of assets is then likely, and the relatively high levels of correlation between equities and credit mean that a sell-off in credit may well occur. In the worst scenarios, the firm with the fake number may default, or it may trigger defaults in those firms betting on it.

The further you are from reality, the harder reality hits you

Investors adjust to the new reality by selling assets and retreating from speculation to limit losses. Losses mount up on any poker tables betting on those investors’ wins, and hit any businesses who make money in dealing with those investors. The real danger then increases as speculation dries up, cashflows wither and a massive directional shift into ‘low risk’ investments takes place.

If concerns are not assuaged – typically due to a lack of transparency around the size and range of exposure – sellers of credit default swaps (CDS) will increase the spreads on new CDS, while also facing larger margin calls to cover the increasing risks of default as credit conditions worsen.

Issuance will dry up and that will have an impact on secondary liquidity and pricing.

In the worst case scenario, if any margin call is too big for the seller to cover, it will default. If this is for cleared CDS, which made up 76% (US$4.1 trillion) of the US$5.2 trillion CDS notional traded in Q2 2025, according to ISDA, then a central counterparty takes on the risk of the position of the defaulted firm. Uncleared trades, the other 21% (US$1.1 trillion) of the US$5.2 trillion notional traded in Q2 2025 – will see the buyer of the CDS exposed to the losses caused by the default of the seller.

Firms exposed to a defaulting party will suffer losses, and depending upon the levels of segregation of monies in the collapsed firm, may find their exposure more or less protected.

The extent to which this would cause a systemic event is limited by two elements; surprise and discipline. The more removed from reality the numbers are, the bigger the surprise to investors and harder they fall. The more disciplined a defaulting party is, the better protected its counterparties and clients’ money will be. The more disciplined investors are, the less exposed to a single event they will be.

But in the words of former Citi CEO, Chuck Prince, “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.” Some players will always try to take the big prizes with greater risk exposure.

The fog of war

Regulators have tried to increase transparency and decrease cascading default exposure from defaults since 2008, but with limited success.

Investors have to seek out greater risks in order to find greater rewards, and they will inevitably come to rely upon a market that has fewer safeguards and less transparency. These are also typically found in smaller markets, like private credit, which should in theory create a smaller risk to the wider market.

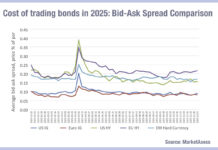

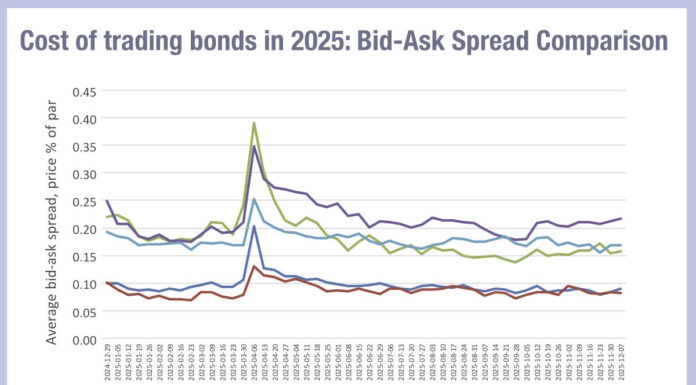

What has definitely improved since the 2008 crash is market liquidity, and that means the capacity to turnover credit as it declines in quality is greatly improved. Electronic trading is less expensive and the boom in availability of high quality data supports manual and electronic liquidity.

The cost of managing liquidity risk has fallen, which helps dealers to better support their clients in a sell-off. Better access to portfolio trading limits the risk of trading the most liquid positions and being stuck with the illiquid debt.

This improvement in market structure has been demonstrated through several events, most notably the Credit Suisse collapse, showing that markets can handle a sell-off when discipline is maintained and surprise is limited.

©Markets Media Europe 2025