Average trade sizes appear to have been increasing in corporate bond markets in recent years. Superficially this might suggest a greater dealer capacity to provide clients with balance sheet. However, it may signify a more profound change.

Average trade sizes appear to have been increasing in corporate bond markets in recent years. Superficially this might suggest a greater dealer capacity to provide clients with balance sheet. However, it may signify a more profound change.

Larger bond trades can face higher execution costs and wider bid-ask spreads, due to the risk carried by dealers in taking on positions that are harder to trade out of, and the greater capital costs in holding a position.

For time-starved buy-side traders, executing the whole order in one go presents a considerable advantage. Assessing the cost / value dynamic is a key skill in the trader’s arsenal.

The tipping point in this is the price discovery process. If the buy-side trader does not read the market well, and approaches too many dealers with detail of the order, information leakage can create problems for the successful counterparty as the market is aware of their new position.

This process is subject to the dynamics of market opacity, dealer concentration, and liquidity constraints. Better pre-trade information offers increased opportunities for frictionless execution. Price transparency is increased by access to dealer axes – indicative guides as to where they are buying or selling bonds today. Yet execution quality varies significantly between dealers, as does the firmness of the axes they provide.

Larger trades typically require more negotiation, frequently necessitating voice or chat discussions, consuming time for the trading desk, and competing with managing primary order flow.

Breaking down orders

The uncertainty around the block trading process can mean that traders may prefer to break orders down to execute in smaller parts that are easier of the market to digest. Not only does this enable faster initiation of trading, it also allows traders to tap into direct price streams with dealers, either supplied via a trading platform or via direct connectivity. Traders may also find that pricing algorithms on platforms are able to automatically execute smaller trades more easily, beginning to take more off the trader’s blotter.

Of course, the risk in this model is that it does not save time if the full position cannot be moved, either due to lack of market appetite or because the market impact of trading out of the position begins to make the buying/selling of the bond unfavourable.

Using all-to-all can let firms reach beyond their usual counterparty list and trade anonymously, thus reducing market impact, which also reduces dealer risks. However, this still may ydrag the teim for execution out.

A third option is to trade some or all of the position within a portfolio trade. Yet this is highly dependent upon the capacity of dealers to consume the size needed within a portfolio trade, and on the liquidity of that security. One portfolio trader from a sell-side firm noted that PT trading was based on the ‘Where’s Wally/Waldo’ model of spotting the element within that should not be there, and removing it before pricing the trade.

If timing is an issue – and if markets are expected to move against the trader, it becomes much more so – trading in larger size is optimal.

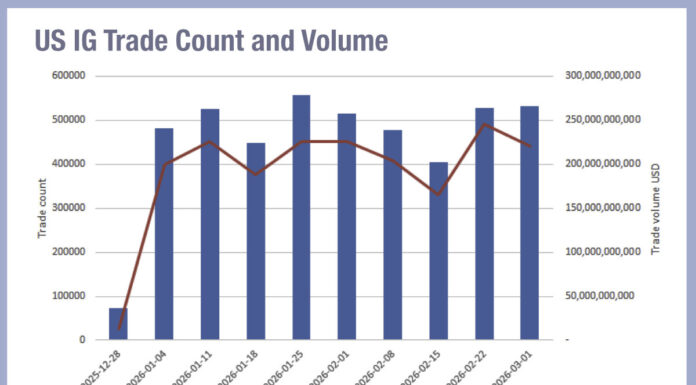

The curious case of the rising trade size

The changing element is that as electronification beds down, average trade sizes across all trading has increased. That is interesting because the proportion of electronification in bond markets has been relatively static over the past two years, which implies it is a change in the quality, not quantity, of trades.

If the level of comfort with electronic execution continues to increase, with market makers pricing larger-sized deals more frequently using electronic trading protocols, it may be that larger-sized trades become a faster as well as more direct route to execution.

Where historically the trade-off between scale and efficiency increased the important of strategic trade planning, transparency initiatives, and regulatory oversight to improve outcomes for large bond transactions, better electronification may allow lower touch execution of blocks, and trader to become more strategically involved in guiding the systems that electronify trades, rather than the trade negotiation.

That could tip electronic trading into a larger proportion of trading, and create critical mass for far more automated execution in bonds.

©Markets Media Europe 2025