The first generation of pre-trade analytics are consolidating; the second generation of price and liquidity providers such as Bondcliq and Katana will need to learn from this if they are to thrive.

The range of pre-trade analytics providers has shrunk in the past six months, with provider Algomi now reportedly being acquired by interdealer broker BGC, following the closure of its rival B2Scan which folded in late 2019. Having formed in 2012, neither was able to achieve profitability independently.

In 2015 their prospects had been good; 54% of traders planned to use Algomi, and 13% planned to use B2Scan according to the Trading Intentions Survey that year. There was an information chasm on bond trading desks. Until a buy-side trader picked up the phone to one or more broker-dealers, they had to rely upon their experience and market knowledge to know who could trade or at what price. Equally, unless the sell-side sales team checked internally they could not be sure what they could buy/sell and at what price.

Their offering, to capture data on pricing and liquidity, then providing analytics to guide traders on where to trade and at what price, had clear benefits to traders. The uptake of some services in this area has been very high. Neptune, which launched as a contemporary of Algomi, providing a standardised electronic flow of dealer axes to the buy-side, has been a notable success.

A second generation of services have now developed in this space. The question will be whether this new generation can create a more viable commercial model for providing this intelligence.

Ownership of data

The issue of data ownership has historically been a thorny one for large data aggregators, including Refinitiv, Bloomberg and exchanges. They have faced calls from traders and dark pool operators – who generate much or all of the data – for lower charges and easier access to it. The counterpoint is always that the aggregated data has value beyond its constituent parts.

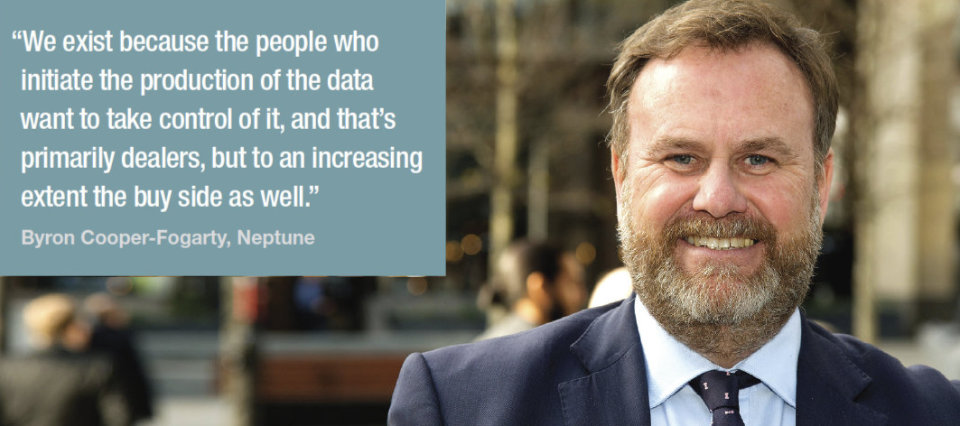

“We exist because the people who initiate the production of the data want to take control of it, and that’s primarily dealers, but to an increasing extent the buy side as well,” says Byron Cooper-Fogarty, interim CEO at Neptune. “As data becomes increasingly important and valuable, it’s really going to be interesting to see how that plays out.”

Neptune initially operated without charging buy‑side firms, but brought in a £16k per year price for the service which has increasingly become accepted.

Smaller pre-trade data providers need to prove that they can deliver a need-to-have service in order to get buy-in from traders for the service they are offering. However, they are challenged at two levels by the existing market structure.

The first challenge is in getting access to data in the first place. Price makers and venues need to see value in streaming their prices via a mediated service.

“Each of the individual trading venues has a very unique view into the marketplace,” says Kevin McPartland, head of market structure and technology research at Greenwich Associates. “And they also increasingly understand the value of the data that they are collecting from traders, so they are not in a hurry to allow another third party to take that data and put it all in one place, as it minimises the value of that asset for them. That made it hard for some of these third-party data providers to come to market, or show the buy side something that’s really enticing.”

Secondly, venue operators are able to use their own data to build services which can support pre-trade decision-making. MarketAxess has developed a composite price (CP+) which has gained considerable support as a mid-point.

David Krein, global head of research at MarketAxess says, “We have seen the adoption of CP+ on the buy and sell side move from being a display point on our screen, to become the foundation of our internal crossing tool in Europe, and also for our auto-execution tool.”

The public data found in US corporate bond markets via the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE), run by Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), a private corporation and self-regulatory body, gives the market a baseline dataset of post-trade bond prices. Although MiFID II attempted to create greater transparency in Europe, it has yet to lead to a similar consolidated tape.

“There is [greater hunger in Europe], because MiFID II in corporate bonds has largely been a miss,” says Krein. “That hole in the market creates demand for data tools. TRACE is not perfect; it is quite unwieldy, it has a lot of moving parts and it hasn’t changed in half a decade. It was in some ways ahead of its time, but as execution becomes more electronic and automated TRACE is less able to fulfil the needs of traders.”

For firms that do not have the data, clever ways are being found to build that information up, in order to deliver a picture of the market that is valuable.

Appetite for change

The need for better tools stems from the conflicts of interest that exist under current models, says Chris White, CEO of Bondcliq, which pulls bid, offer and size data together and feeds it to the buy side, with dealers given feedback on the quality of the prices they are making.

The need for better tools stems from the conflicts of interest that exist under current models, says Chris White, CEO of Bondcliq, which pulls bid, offer and size data together and feeds it to the buy side, with dealers given feedback on the quality of the prices they are making.

“The approach to data up to this point has been privatised micro-networks of data in the institutional markets,” he says. “The main problem with that is that you are not improving; when you have a privatised network of data the reliability of that data for trading is automatically corrupted. If you play poker and you are the only one that gets to see the flop, there isn’t going to be a lot of action on the poker table.”

Santiago Braje, CEO of Katana, which offers an AI-derived bond price, argues that there is also increasing demand stemming from the changing execution model.

“We come from a market that was essentially built on bilateral relationships and trust,” he says. “Historically a PM would work with some banks that they would trust and regularly would get liquidity from. The industry is still organised as if things continue to work like that, but this is not the reality anymore. Those trust-based relationships where effectively you would get a different price from everyone else, because the dealer would make different prices to different people, is in a transition period.”

He sees this transition as characterised by the joint trading styles of smaller electronic orders pushed out to multiple dealers in competition, in a relatively transparent model, with block trades happening via voice or in non-comp dark trading.

“This move from analogue to digital reflects a shift from bilateral communications to multilateral communications,” he argues. “It was fairly easy to make that change for smaller trades, it’s much harder for blocks because information is much more sensitive. So you don’t put things out there for everyone to see, because it works against your own position.”

Path to success

Certainly, buy-side traders are becoming more open to new ways of consuming data, in no small part driven by increased opportunities for electronification or automation of the trading workflow.

“We have found the way the buy side consumes data, particularly larger asset managers, has gone from being GUI-based to more API-driven,” says Cooper-Fogarty. “Over the last 12 to 18 months most of our users have gone from accessing data through our GUI, to connectivity either via an OMS, an EMS or a data aggregator such as ALFA. Over a third of our clients now use direct APIs, although our clients will often consume Neptune data through multiple connections.”

The make-up of data users via Neptune has also changed, with 80 per cent being traders and 20 per cent increasingly portfolio managers and research analysts.

White sees increased connectivity with trading tools via APIs as an enabler to success, where traders were once the only users.

“Our next obstacle is not to get the dealers to share the data, it’s to get the dealers to interact with the data seamlessly,” he says. “So we are now plugging into the dealer systems, the pre-trade data. Why a buy-side trader should care is because the integrity of the data is directly linked to whether or not the dealers can see the position of the price. Dealer visibility equals dealer confidence, equals more reliable institutional liquidity, that’s the way we see the world.”

©The DESK 2020

©Markets Media Europe 2025