A regulatory shadow hangs over the market as agencies battle to contain the impact. Chris Hall reports.

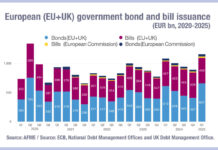

As part of the European Commission’s efforts to deliver a harmonised post-trade experience across Europe, Central Securities Depository Regulation (CSDR) will impose T+2 settlement by 2023. It will also eliminate settlement fails both by imposing fines for non-delivery, plus time-limited mandatory buy-ins.

European fail rates in government and corporate bonds currently run at just under 3% by value according to the 2019 European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities. Pre-existing guidelines for discretionary buy-ins, drafted by the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), are already used as a last resort, if a seller cannot deliver the securities promised to the buyer.

But the time limits imposed via a mandatory buy-in increase the chances of a buy-in agent paying a different price to secure the substitute securities, especially if illiquid instruments or volatile market conditions are involved. Further, while discretionary buy-ins require counterparties to compensate each other for price movements, leaving the original trade’s economics unchanged, CSDR’s mandatory process only allows for payment of any differential between the original and buy-in prices from the seller to the purchaser, meaning the seller loses out if the buy-in price is lower than the original trade price.

Scheduled for September 2020, many fear the outcome asymmetry introduced by CSDR’s settlement discipline regime will create unpalatable risks for market makers, resulting in a major withdrawal of liquidity. Others point to a lack of clarity on the scope and mechanics of the regime’s mandatory buy-in process, fretting there is now insufficient time to achieve compliance, even in the event of a MiFID-style delay. Calmer voices suggest too much fuss is being made of the wonky third leg of Europe’s securities market infrastructure reforms, especially when other markets, notably in Asia, function perfectly well with a zero-tolerance attitude to settlement fails.

Backed by numbers

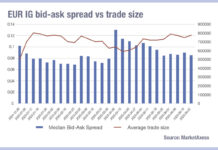

In November, an ICMA survey found that 84% of buy-side, sell-side and repo desk respondents expect mandatory buy-ins to ‘worsen’ or ‘worsen significantly’ market efficiency and liquidity. Widening spreads across all bond sub-classes are predicted to hit covered bonds and illiquid investment grade credits hardest (widening by 250% and 225% respectively for five-year maturities), with absolute price increases most notable in illiquid investment grade corporate and high yield bonds. In addition, 83% of respondents said mandatory buy-ins would have a negative impact on securities financing markets.

“Our survey provides clear evidence that the extra risks and costs introduced by mandatory buy-ins are likely to have a significantly detrimental impact on liquidity provision. Market makers will withdraw liquidity and spreads will widen. There is a real danger that CSDR will create trading-by-appointment markets in certain less-liquid fixed-income instruments,” says Andy Hill, senior director for market practice and regulatory policy at the ICMA.

“Our survey provides clear evidence that the extra risks and costs introduced by mandatory buy-ins are likely to have a significantly detrimental impact on liquidity provision. Market makers will withdraw liquidity and spreads will widen. There is a real danger that CSDR will create trading-by-appointment markets in certain less-liquid fixed-income instruments,” says Andy Hill, senior director for market practice and regulatory policy at the ICMA.

For Christoph Hock, head of multi-asset trading at Union Investment, the outlook is more nuanced. “Liquidity is an important topic in both the credit and sovereign bond markets, but we’re not getting a consistent view on CSDR’s impact from brokers at present,” he observes. “Some say their market-making operations will still be able to price aggressively in the names in which they’re active, due to the diverse range of liquidity pots they can access. Others are highly concerned about the risks of failing to deliver under the new regime. Asia’s example suggests it might not be as bad as we feared, but nor is it supportive of liquidity and pricing.”

To mitigate potential negative impacts, ICMA survey participants favoured exemptions for all or at least illiquid bonds from mandatory buy-ins, whilst other remedies, e.g. longer extension periods, removing asymmetry and relaxing the requirement to appoint a buy-in agent, also found support. Even at this late hour, ESMA may permit Level 3 guidance allowing trading parties to settle a buy-in or cash compensation differential symmetrically via contractual arrangements. Also, ESMA is expected to back an ICMA-drafted proposal for a pass-on mechanism to avoid fails triggering multiple buy-ins when a transaction is part of a chain across multiple counterparties.

Big risks

But remaining practical uncertainties hamper preparations. “There are still many areas where more clarity is required from regulators, including which instruments will be included in the three extension periods,” says Silvano Stagni, director of regulatory consultancy PMCR. When a CSD confirms a settlement fail under CSDR, it first triggers an extension period of four, seven or 15 days to resolve the matter before the mandatory buy-in is initiated. It is not yet known which instruments will fall into the three liquidity buckets, but uncertainty also hangs over counterparty responsibilities and information flows as a rare occurrence becomes more common.

But remaining practical uncertainties hamper preparations. “There are still many areas where more clarity is required from regulators, including which instruments will be included in the three extension periods,” says Silvano Stagni, director of regulatory consultancy PMCR. When a CSD confirms a settlement fail under CSDR, it first triggers an extension period of four, seven or 15 days to resolve the matter before the mandatory buy-in is initiated. It is not yet known which instruments will fall into the three liquidity buckets, but uncertainty also hangs over counterparty responsibilities and information flows as a rare occurrence becomes more common.

Phil Slavin, COO and co-founder of Taskize, a workflow solutions provider, says existing tools and processes may fall short. “It is not always entirely clear which party is responsible for the settlement fail and who should receive the penalty,” he says. “Under CSDR, CSDs have ultimate responsibility for the management of settlement fails, including the issuance of penalties, but there are plenty of grounds under which fined parties may not take that decision at face value. They will have their own view of the situation that leads to the penalty, which may lead to an increase in disputes.”

There are also questions over the role and preparedness of CSDs and buy-in agents. “Discussions are ongoing to decide upon the notification process to be used for the buy-in process,” says Alexia Kazakou, global product development manager, Citi Securities and Fund Services. “Clarity has also been sought on the definition and roles of buy-in agents to avoid potential conflicts of interest. Indeed, there are many open items to be resolved that even a potential delay to November 2020 may still not provide the industry sufficient time to prepare adequately.”

Both on the buy- and sell-side, the lack of clarity is a signal to avoid fails at all costs, by exercising greater control and oversight over both trading processes and inventory. Chris Perryman, head of trading, portfolio manager, EM specialist, Pinebridge Investments, sees CSDR in the context of the fixed income market’s gradual post-crisis readjustment to a new liquidity reality. Market participants should factor in the liquidity premium to their transaction costs as well as the credit spread, says Perryman, albeit admitting the transition to greater transparency may not be smooth.

“Many buy-side trading desks in Europe seem to take liquidity for granted, rather than regarding it as something that needs to be managed proactively. To this end, our front office is involved in the investment process from start to finish, including updates on matching throughout the trading day,” he says.

An integral part of this new liquidity reality is the freeing up of buy-side inventory. “To address broader liquidity challenges in the fixed income markets, the buy-side needs to reconsider its approach to the repo and securities lending markets, with a view to making some of their ‘buy-and-hold’ assets more available. Many firms stepped away from lending during the 2008 crisis, but I sense that some are becoming more comfortable with the activity again,” says Perryman.

An integral part of this new liquidity reality is the freeing up of buy-side inventory. “To address broader liquidity challenges in the fixed income markets, the buy-side needs to reconsider its approach to the repo and securities lending markets, with a view to making some of their ‘buy-and-hold’ assets more available. Many firms stepped away from lending during the 2008 crisis, but I sense that some are becoming more comfortable with the activity again,” says Perryman.

To this end, market participants will be hoping that ESMA supports an ICMA proposal for open securities financing transactions to be ruled out of scope of CSDR.

©The DESK 2019

©Markets Media Europe 2025