Lynn Strongin Dodds explains why Europe cannot look to TRACE as a role model.

Developing a consolidated tape for fixed income in Europe was never going to be easy but MiFID II only seems to complicate matters. The USA’s Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) may serve just as an inspiration but not a prototype for Europe’s fragmented markets and idiosyncrasies.

To begin with, only a small percentage of outstanding securities are impacted by MiFID II’s pre- and post-trade publication requirements. Trades in sovereign bond issues are only covered if the initial size of the offering is greater than €1 billion, while corporate and convertible bonds are only subject to price transparency for issues of €500 million or more.

Recent numbers crunched by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) estimate that a mere 566 bond instruments out of 61,761 were sufficiently liquid to fall under the new pre- and post-trade transparency rules. The majority are sovereign bonds while only 157 out of 39,000 corporate bonds were labelled as liquid.

Those that meet the liquidity thresholds have to publicise their prices to request for quote (RFQ) in real time, and post-trade the execution time, venue, ISIN, price and notional have to be disclosed as near to real-time as possible. Their illiquid brethren are under no obligation to make their pre-trade quotes public and post-trade reporting can be between two days or up to four weeks depending on the national regulator.

Moreover, there are many different moving parts in the reporting landscape. There are not only the approved reporting mechanisms (ARMs) which have to report details of transactions to competent authorities but also approved publication arrangements (APAs) which publish post-trade transparency reports on behalf of investment companies. In the UK, the latter group includes Abide Financial, Bats Trading, Bloomberg Data Reporting Services, London Stock Exchange, Tradeweb Europe and Xtrakter.

There is also a new category of consolidated tape provider (CTP) which will come into existence next January. The aim is for them to collect post-trade transparency reports from regulated venues and APAs and consolidate them into a continuous electronic live data stream providing price and volume information per financial instrument.

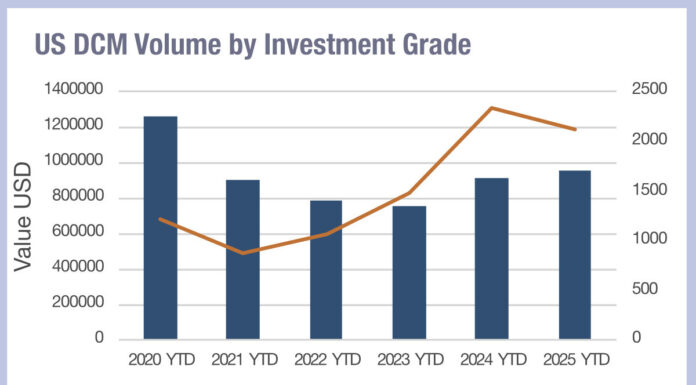

By contrast, TRACE was launched by one entity – the US Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (Finra) – in 2002. It started publishing the price and volume of investment-grade, high-yield, and convertible debt before expanding its coverage to asset and mortgage-backed securities, US government agency debt, and primary transactions in corporate debt. Unlike, MiFID II, there is no pre-trade reporting or disclosure requirement.

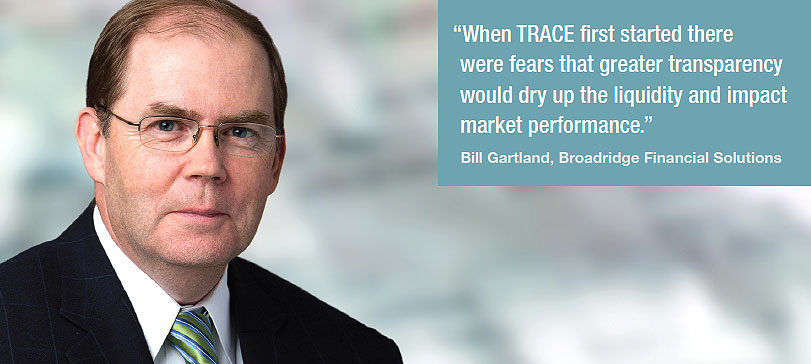

“When TRACE first started there were fears that greater transparency would dry up the liquidity and impact market performance,” says Bill Gartland, vice president, fixed income data and analytics at Broadridge Financial Solutions. “However, TRACE has been positive in terms of providing a better view of pricing and valuations. Traders can extrapolate the information to bonds that are not that easy to trade.”

The benefits have been underpinned by a plethora of academic studies that show transaction costs for bonds eligible for TRACE reporting fell roughly 50% immediately following its introduction while others, such as Bessembinder and Maxwell’s Transparency in the Corporate Bond markets, note that “investors have benefited from the increased transparency, through substantial reductions in the bid-ask spreads that they pay to bond dealers to complete trades.”

As for the downside, there is the 2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology study, The Effects of Mandatory Transparency in Financial Market Design: Evidence from the Corporate Bond Market. It acknowledges the improved price discovery, but also found that trading activity in the US corporate bond market was reduced, especially amongst already illiquid high yield bonds. They reported a 41.3% slide based on volume/issue size, against 15.2% across all bonds. Other criticisms include the steady migration to agency from principle trading since its inception.

Lessons learned

Buy-side participants would welcome a European consolidated tape although the general consensus is that the TRACE format would be difficult to replicate in Europe.

“TRACE has had an advantage in that there is one regulated body in charge of one market and oversight of one country which has made it a less politically complex system,” says Joe Grochan, global head of data solutions at MarketAxess. “They adopted a gradual and structured approach to the market segments covered. There were also no liquidity classifications and all information was released by market segment. In Europe, to date, less than 5% of the corporate bond market is being reported under MiFID II.”

Grochan adds that TRACE segmented the release of information by market, while MiFID II is segmented by liquidity classifications. This is an important difference because firms tend to be structured by market. “From a cost benefit point of view, firms would prefer 100% of one market versus 5% of all markets,” he adds.

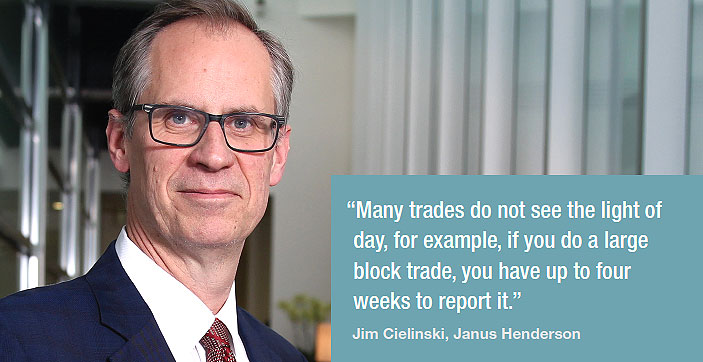

Jim Cielinski, global head of fixed income at Janus Henderson also believes that “lessons have been learnt from TRACE and transparency is good for the markets but MiFID makes it more complex in that there is fragmentation with six APAs collecting data from different venues and both the buy- and sell side have to contribute.”

He adds that “the other issue is the quality of data, because aggregation is only as good as the data behind it. One of the problems is that many trades do not see the light of day and for example, if you do a large block trade, you have up to four weeks to report it. I think these are some of the biggest shortcomings when talking about developing a consolidated tape in Europe.”

Another stumbling block is the lack of a common messaging language across the different fixed income venues. “This makes it difficult to aggregate the transaction data and provide a holistic picture of the fixed income market,” says Matthew Hodgson, Mosaic Smart Data. “However, even if there were protocols, it may be difficult for them to gain traction and create a consolidated tape. The provision of data is highly commercial and their incumbents find ways to provide more unique data.”

ESMA to take up the CT gauntlet?

For now, a consolidated tape in Europe is still a pipedream and it is difficult to predict if and when it will materialise. As Gartland notes, it makes sense for Europe to have one because it is important to have robust information for analytics, price discovery and transaction costs analysis. “However, I can’t say when it would happen and there are valid reasons why it will take time,” he adds.

If it does materialise, there are calls from some quarters of the industry for ESMA to take charge. Last year, a European Commission expert group published a report – Improving European Corporate Bond Markets – which called upon the regulator to create a service for corporate bonds that is accessible to market participants at a reasonable cost.

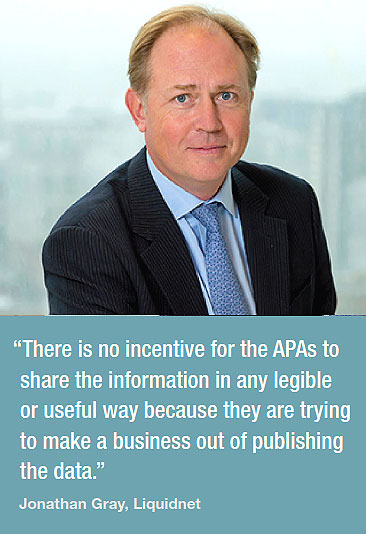

“I think the market would like ESMA and not a third party to be responsible because it would add authenticity to the tape,” says Jonathan Gray, head of fixed income for EMEA at Liquidnet. “The buy side would like one because they are not happy to have the data being sold back to them, but there is no incentive for the APAs to share the information in any legible or useful way because they are trying to make a business out of publishing the data.”

He adds, “There clearly needs to be more transparency in the credit markets to make it work. At the moment, too many bonds are in the illiquid category, with a two day reporting delay, to make trade reporting meaningful because you do not see the real time pricing.”

©Markets Media Europe 2025