Banks’ support for market making is tied to the bonds they carry on their books, and the cost that has for their balance sheets. Crudely speaking, as they increase holdings of risky and / or illiquid assets, their costs go up.

The DESK has found – via primary research and anecdotal evidence – that liquidity provision for the typical investment manager has worsened over the past year.

However, finding a correlation between bank holdings and liquidity provision is more challenging.

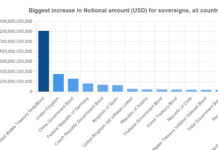

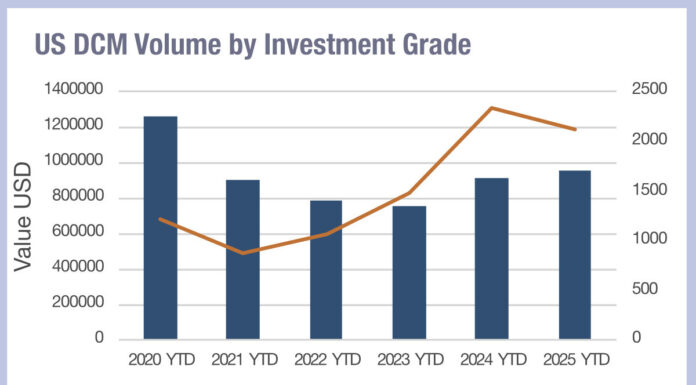

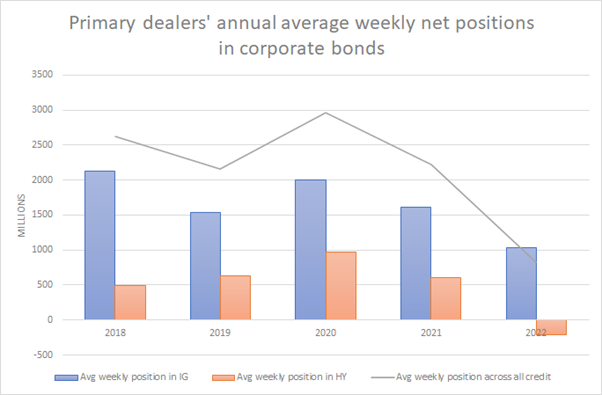

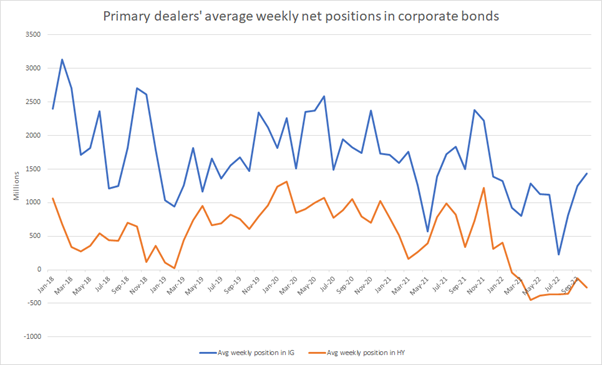

We see that average positions of corporate bond holdings amongst the 25 primary dealers in the US have fallen over the past five years. That potentially supports the picture that higher costs of capital for risk assets are driving down holdings.

Based on a review of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s data, to which the 25 primary dealers are required to report, their average weekly positions five years ago were three times higher than their current level, year to date.

The Fed’s data, which provide a net view of positions based on long (bought) and short (sold) shows the greatest reduction in positions has been in high yield, which have been negative since February 2022.

As the data does not provide the user with the gross holding that banks have, only their net positions (hence negative positions being reflected), they may have been engaged in a more balanced level of buying and selling in 2022 than other years.

If we assume that the positions held are correct balance sheets are likely to have been more stretched in 2020, when investment grade and high yield average net positions were over three times greater than in 2022.

Another measure we can consider is the level of debt holding from ‘hung deals’ they have been left with to support certain corporate M&A activity, including the recent US$44 billion Twitter takeover. Based on the ‘Project X’ commitment letter filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on 22 April 2022, banks have US$12.5 billion of debt underpinning the deal that they have been left holding.

Christian Bolu, analyst at Autonomous Research recently asked Morgan Stanley’s chief financial officer Sharon Yeshaya about this.

“You guys seem to be on a number of hung deals, Citrix, Twitter, et cetera,” he said. “So first of all, how big is your bridge book or leverage loan book, however you want to characterise it? And then second, are you increasing your risk appetite here to capture opportunities? And then how are you thinking about managing that risk?”

Yeshaya replied “Broadly speaking, I’d say we’ve been extremely prudent in terms of risk management. I think that’s most notable actually when you think about our risk weightesd assets (RWAs) and our capital position. We’ve been looking at different risk-based metrics really over time and bringing them down over the course of the year. So that’s for the entire institution, just knowing that we’ve entered into what feels like a more volatile period. And as you think about those different relationship and event net of hedges, over the course of this quarter, they actually were quite modest marks, given the environment.”

Looking at the 2022 data for primary dealers the average weekly position for investment grade debt would be a net US$40 million based on long and short activity. However, that figure does not represent a gross holding of bonds, nor can it accurately represent the balance of holdings between larger firms and smaller dealers in the primary dealer space.

Jesse Rosenthal, head of US Financial at analyst firm CreditSights, believes holdings based on hung deals are unlikely to be all that significant.

“Firstly, the size of hung deals is actually not all that large,” he says. “We’ve done work with our colleagues over on the LSI side even before some of the deals started closing recently, and the total hung book value was something like a 10th of what we were looking at in precipitating the global financial crisis.”

“Secondly,” he continues. “Even though there’s close to US$13 billion for the Twitter deal, which is a large headline number, there’s a ton of banks on that. Even if you presume a 20% share, US$2.5 billion, you’re talking about a pretty incremental amount of capital that has to get allocated. From a funding perspective, loans that the banks are keeping on the balance sheet will mostly be part of the corporate bank, and I presume funded primarily from deposits. Market making inventories tend to be secured finance. And so, again, excess liquidity on the deposit side goes to help fund these loans, that they’re going to keep on their balance sheet for a little longer.”

However, it is fair to say that if risk appetites fall – which chimes with both research and current reported positions – while debt is being held on the balance sheet unintentionally, then some banks may be even more reluctant to support liquidity than usual. As globally systemic important banks (G-SIBs) have their capital surcharge calculated at year end, this may prove to be a greater deterrent to risk taking.

“My personal view, is that the timing of the calendar is that the G-SIB recalculation might impact the appetite for banks to increase inventories and marketing, because we typically see a pullback in balance sheet over the last couple of months of the year, in anticipation of that year end GSIB recalculation,” says Rosenthal.

©Markets Media Europe 2022

©Markets Media Europe 2025